This is the third part of a week-long series of guest posts on mind mapping by Hobie Swan, a professional writer from Boise, ID. Mr. Swan is interested in helping teachers find ways to incorporate this strategy into the classroom. This part focuses on improving student writing.

Students swim in media-rich waters

One of the keys to good writing is good preparation. But rare is the student who loves to dig into that most important of preparatory documents: the outline. I tend to think of it more as a “pre-writing document.” When most people think of outlines, they imagine line upon line of text. A pre-writing document is something more befitting the resources students have at their disposal these days.

Kids live in a media- and information-soaked culture. To require them to work in a landscape dominated by text may seem to some akin to carving their thoughts on the tusk of a whale. More appropriate--at least for the pre-writing phase--may be to give them the tools to create rich, multimedia aggregations of insights, images, and information. As I will explain, this may require no more than giving them access to a single mind-mapping application.

Start with divergent thinking

Creation of the standard outline may well be a prime cause of the dreaded blank page syndrome. Even the most seasoned writer can falter when faced with the gaping maw of a blank screen. What, the emptiness taunts, is that one very first thing you want to address. It’s too much pressure. Who know what they want to think of first, then second, then third.

A new mind map, while still nearly blank, offers one small, lifeboat-shaped haven. In the center is a small shape into which you can enter a word or two to describe the purpose of the map.

Let’s call this map: Memoir. For this writing assignment, you have asked your students to write something about a memorable event in their lives.

This might still seem intimidating until the student realizes that they don’t have to start a numbered list of their thoughts, with the first one on tope, followed by the second, third, etc.—proceeding in a relentlessly linear way until they reach The End.

Instead, your first suggestion to your students can be for them to think of some memorable event and just start brainstorming: jotting down ideas as they pop up in their brains:

Many students I’ve talked to say that the ability to add images helps make the assignment for fun, more engaging. Being able to just quickly jot down ideas makes the process more open and creative. And that can lead to new insights. See how in the next map the student has begun to interact with his or her idea.

Move on to convergent thinking

Mind mapping is a great way to get students’ minds thinking. By first being able to just think random thoughts, they can feel less constrained. They can let their minds wander as they please in and around the topic at hand.

Usually, this allows a main thesis to emerge—and for less important or unrelated ideas to depart. In this example, seeing all of the ideas on one screen has given the student insight into what exactly he or she is thinking about. In this case, the student seems most interested in the teacher, and how he or she made the year so memorable:

The student has dragged and dropped the branches from his first use of the map, added some new ideas and, in the process, and converged their thoughts on one main idea.

Mind mapping methodology allows room for this kind of divergent-to-convergent thinking that is often missing in student writing.

Now to form an organized whole

Once some ideas have been captured and perhaps an inkling of insight gained, it is time to leave the free thought behind and start creating a logical structure for the ideas and information that will make up the final writing. Some mind mapping products (and again, ConceptDraw is one such product) allow users to see or to export the map contents in more traditional outline form:

If the student so chooses, he or she can simply push a button to export the map as a traditional outline, and continue the writing process:

It is fair to say, though, that once your students (or you yourself) get used to working in this more concise, visual way, they may be more inclined to continue to flesh out their ideas right in the map:

… knowing that at any point they can export what they’ve written as a working outline:

One example among many

I’ve used a creative writing assignment as the topic. Regardless of the topic and hand, mind mapping’s ability to integrate multimedia and interactivity allow students to work much more quickly, intuitively and, I would argue, more creatively.

As I noted in the first article in this series, ConceptDraw MINDMAP enables users to embed hyperlinks, images, multimedia, and graphics into a pre-writing document. Students can browse the Internet, link to research resources, and then combine online information with information from other sources—including their own ideas—to enable them to do the kind of preparation that can lead to more reasoned arguments and less head-scratching on the part of teachers.

And again, mind mapping enables students to work in a very information-rich way, with access to all the many forms that information comes in these days. That includes everything from websites, to images and icons, to YouTube videos and information clipped from Facebook or Twitter. Most important of all, mind mapping is designed to help people collect all of this rich information—and then add to it their own insights, reactions, and observations of that information.

It is in delivering a true 21st century mixture of pre-existing information and new ideas that mind mapping shines.

Read the other entries in the series:

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: The Chunking of Language

Part 4: Improving Research

Information, inspiration and ideas to help teachers in and out of the classroom

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Mind Mapping for Teachers, Part 2: Chunking of Language

Tags:

curriculum ideas,

mind mapping

This is the second part of a week-long series of guest posts on mind mapping by Hobie Swan, a professional writer from Boise, ID. Mr. Swan is interested in helping teachers find ways to incorporate this strategy into the classroom.

As I writer, I can easily bristle at the idea of our trading in the well-crafted sentence for a few well-considered words. If it wasn’t so handy, I’d be a lot more resistant to this practice. But because of the visual nature of a mind map, people tend to use words much more sparingly that they do when writing a document (such as the one you’re reading right now that may seem to be droning on and on). What might otherwise take a paragraph to communicate can be done using just a sentence or phrase--maybe even in one single word--when you mind map.

This makes the information in the map:

Today’s students live in a world filled with motion and images. For many of them, nothing could be more boring that having to reduce all of that excitement and action to “a page and a half” of writing. But turn them loose with a mind map, in which they can quickly capture and organize elements of the information sea in which they swim, and you may be surprised at what they come up with.

Read the other entries in the series:

Part 1: Introduction

Part 3: Improving Student Writing

Part 4: Improving Research

As I writer, I can easily bristle at the idea of our trading in the well-crafted sentence for a few well-considered words. If it wasn’t so handy, I’d be a lot more resistant to this practice. But because of the visual nature of a mind map, people tend to use words much more sparingly that they do when writing a document (such as the one you’re reading right now that may seem to be droning on and on). What might otherwise take a paragraph to communicate can be done using just a sentence or phrase--maybe even in one single word--when you mind map.

This makes the information in the map:

- More easily understood: Children for whom English is not their native language, with dyslexia, or low literally levels often find it far easier to understand what is being communicated—and more able to interact with the information.

- Contexually powerful: Because of the spatial nature of a map, the viewer finds context by seeing where a concept is relative to its neighbors. Communicating without these visual cues means that all meaning must be expressed using words—and we are back to the multi-page document.

- Concise: Because the map is built with individual branches made up of a few words and maybe an image or icon, it’s possible to capture up to 10 or so pages of writing in one map. The ability to see all of the information in one view improves the ability to interact with that information. Note: Map branches can be “collapsed” so that the document isn’t cluttered with information you don’t need at any given moment.

- Quickly digested: You plow through a written report. You scan a map.

- Flexible: I’ll discuss this further in the article about writing. The main point is that by capturing information onto individual branches, the information can be quickly and easily dragged and dropped into similar groups, chronological order, or any other arrangement that best suites the current objective.

Today’s students live in a world filled with motion and images. For many of them, nothing could be more boring that having to reduce all of that excitement and action to “a page and a half” of writing. But turn them loose with a mind map, in which they can quickly capture and organize elements of the information sea in which they swim, and you may be surprised at what they come up with.

Read the other entries in the series:

Part 1: Introduction

Part 3: Improving Student Writing

Part 4: Improving Research

Monday, November 28, 2011

Mind Mapping for Teachers, Part 1

Tags:

curriculum ideas,

mind mapping

This is the first in a week-long series of guest posts on mind mapping by Hobie Swan, a professional writer from Boise, ID. Mr. Swan is interested in helping teachers find ways to incorporate this strategy into the classroom.

In this multi-part series I will describe a few ways to use mind mapping in teaching. I will talk about how teachers can use mind mapping to make their work easier and clearer, and how students can use mind mapping to help them organize thoughts and information.

The three uses I will describe are:

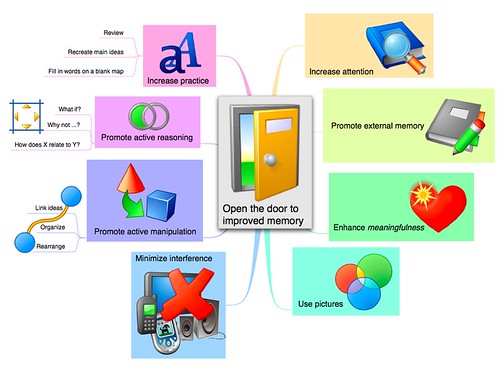

A note on the history and development of mind mapping

Some say that the practice of mind mapping is as old as the hills. It is, indeed, possible to find quite old examples of what is often referred to as “visual thinking”—the theory behind mind mapping. There has been much evidence to support the main tenet of visual thinking that the mixture of text and images promotes thinking and learning. Much of the rationale for this theory comes from Robert Sperry’s Nobel Prize-winning experiments with people whose two brain hemispheres had become separated. Sperry’s experiments revealed some of the specialization of the brain, and how by stimulating more than one functional part of the brain, we increase the creative and memory capabilities of the brain.

From these origins grew the highly sophisticated practice known today as mind mapping. This manner of capturing, organizing, and sharing mixtures of information, ideas and images is today used by everyone from English and German school children to 85 of the Global Fortune 100 companies.

Its use in academics has yet to be fully taken advantage of. One barrier continues to be the ability of students and teachers to have unfettered access to computers, computer software, and the Internet. For the purposes of this series, I will assume that you and your students access to all three.

Creating Multi-Media Lesson Plans

A common thread you will see in all of the uses I discuss is a teacher’s ability to combine multiple information type in a single, easily constructed and navigated document. A mind-mapped lesson plan often includes:

Download a full example with step-by-step instructions and screen captures via Google Docs.

A Symphony of Meaning

“But what,” you might ask, “are the advantages or creating a lesson plan this way? It seems like it would be easier to do this as a word document?”

One of the results of Sperry’s research was that each hemisphere of the human brain is better suited to particular forms of information. Traditionally, the left hemisphere has been thought of as the home of reason, logic, numbers, and language. While the right side excels in rhythm, color, images, and intuition. Provide information is a way that appealed to as many of these cross strengths as possible, it was believed, and the brain would be more able to learn, remember, synthesize, and create.

As this idea has gained popularity over the years, so has the idea that some people’s brains are better able to take in information captured in one of these way (i.e. some of us are “visual learners.” More recently, research suggests that we all think better when information is communicated using these different modalities. Yes, a picture is worth a thousand words. But a picture with a caption written in bold red type with an exclamation point is worth a lot more.

Read the other entries in the series:

Part 2: The Chunking of Language

Part 3: Improving Student Writing

Part 4: Improving Research

|

| Screen capture of an example "starter" mind map (ConceptDraw MINDMAP software) |

The three uses I will describe are:

- To create multimedia lesson plans.

- To help students organize their writing.

- To help students conduct research.

A note on the history and development of mind mapping

|

The “Tree of Love” by Porphyry of Tyros (3rd Century AD, Greece) |

From these origins grew the highly sophisticated practice known today as mind mapping. This manner of capturing, organizing, and sharing mixtures of information, ideas and images is today used by everyone from English and German school children to 85 of the Global Fortune 100 companies.

|

| Images and observations of early life by Leonardo da Vinci (15th Century AD, Italy) |

Creating Multi-Media Lesson Plans

A common thread you will see in all of the uses I discuss is a teacher’s ability to combine multiple information type in a single, easily constructed and navigated document. A mind-mapped lesson plan often includes:

- A thesis statement and accompanying questions

- Active internet links

- Images and icons

- Answers and notes

Download a full example with step-by-step instructions and screen captures via Google Docs.

A Symphony of Meaning

“But what,” you might ask, “are the advantages or creating a lesson plan this way? It seems like it would be easier to do this as a word document?”

One of the results of Sperry’s research was that each hemisphere of the human brain is better suited to particular forms of information. Traditionally, the left hemisphere has been thought of as the home of reason, logic, numbers, and language. While the right side excels in rhythm, color, images, and intuition. Provide information is a way that appealed to as many of these cross strengths as possible, it was believed, and the brain would be more able to learn, remember, synthesize, and create.

As this idea has gained popularity over the years, so has the idea that some people’s brains are better able to take in information captured in one of these way (i.e. some of us are “visual learners.” More recently, research suggests that we all think better when information is communicated using these different modalities. Yes, a picture is worth a thousand words. But a picture with a caption written in bold red type with an exclamation point is worth a lot more.

Read the other entries in the series:

Part 2: The Chunking of Language

Part 3: Improving Student Writing

Part 4: Improving Research

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Happy Thanksgiving! Get 25% Off My Books

Recently I received an email with the subject line "Your book is phenomenal!" Okay, I thought, I'm listening:

Get 25% off my books now through December 14th: Go to my Author Spotlight on Lulu.com, order a book (or two), and enter the code BUYMYBOOK305 at checkout.

Have a great holiday!

Dear Tom,Ryan is referring to my first book, Ten Cheap Lessons. This is one of the best compliments I've ever received, and it came at a time when I was struggling at school and needed the boost. In the spirit of Thanksgiving, I'm excited to share a great deal on either of my books:

I just wanted to shoot you an email to tell you that I love your book. It has so many fantastic ideas that I already have implemented in my classroom. As a fellow teacher, our job can be a little overwhelming at times because we need to both really engage the students and also get them to learn the material. Many people can do one of the two things mentioned, but it takes a really hard-working teacher to do both simultaneously. Your book has really provided me with a lot of different ideas and I just wanted to say thank you. I really appreciate you publishing it and making it so easily accessible to anyone. I use your website/blog and I purchased your book on my iPhone so that it is always in my pocket. Thanks again!

Ryan Smith

Mathematics Teacher

Get 25% off my books now through December 14th: Go to my Author Spotlight on Lulu.com, order a book (or two), and enter the code BUYMYBOOK305 at checkout.

Have a great holiday!

Monday, November 7, 2011

Equations vs. Inequalities Mini-Poster Project

The first chapter in my first book is entitled "The Mini-Poster," so it should be no surprise that it's a favorite that I constantly adapt to new topics. This time around, I wanted to do a "six weeks" project to wrap up the grading period in Algebra I, where we've been working on solving equations and inequalities.

In this project, students make four mini-posters (one 8.5" by 11" page each) for four (technically seven) types of problems:

By forcing them to do the mirror-image problems, the message is explicit: you solve both problems with the same steps. Along with reviewing all of the problems, the purpose of this project is indeed to draw the clear connection between solving the two types of problems. I told students to keep the title and "how to solve" sections the same as what's on the directions, but to change the examples (helpfully outlined in boxes) to their own

Regular readers will probably note that this isn't all that different from the Linear Equation Formula Book project I shared last week; indeed, one student that I have in both classes made the same connection fairly quickly. That's because it's not really all that different. But that's okay.

Download a PDF of the project directions here:

Here are some of my earlier mini-poster ideas for you to draw from:

In this project, students make four mini-posters (one 8.5" by 11" page each) for four (technically seven) types of problems:

- One-step equations and inequalities

- Two-step equations and inequalities

- Multi-step equations and inequalities

- Special case for inequalities (when you have to flip the inequality sign)

By forcing them to do the mirror-image problems, the message is explicit: you solve both problems with the same steps. Along with reviewing all of the problems, the purpose of this project is indeed to draw the clear connection between solving the two types of problems. I told students to keep the title and "how to solve" sections the same as what's on the directions, but to change the examples (helpfully outlined in boxes) to their own

Regular readers will probably note that this isn't all that different from the Linear Equation Formula Book project I shared last week; indeed, one student that I have in both classes made the same connection fairly quickly. That's because it's not really all that different. But that's okay.

Download a PDF of the project directions here:

Here are some of my earlier mini-poster ideas for you to draw from:

- Project Idea: Independent vs. Dependent Variables - the original (I feel like this constitutes a "classic" at this point)

- 2 More Mini-Poster Ideas

- Project Idea: Linear Functions Mini-Poster

Friday, November 4, 2011

Weekend Reader on Classroom Blogging & Writing

Tags:

five for friday

How to Start Blogging with Students [Educational Technology in ELT]

Using Blogs to Engage English Language Learners [Edutopia]

Talker's block [Seth Godin] - The prolific, best-selling writer reminds us that the best way to get better at writing is to practice every day, as much as possible. He suggests setting up some kind of public blog, which is good advice. If you were working with high school students on writing, this would be a good article for them to read.

Harness the Mental, Creative, and Emotional Benefits of Regular Writing [Lifehacker]

How to create a Digital Publishing Culture [Connect! via Twitter]

Using Blogs to Engage English Language Learners [Edutopia]

Talker's block [Seth Godin] - The prolific, best-selling writer reminds us that the best way to get better at writing is to practice every day, as much as possible. He suggests setting up some kind of public blog, which is good advice. If you were working with high school students on writing, this would be a good article for them to read.

Harness the Mental, Creative, and Emotional Benefits of Regular Writing [Lifehacker]

How to create a Digital Publishing Culture [Connect! via Twitter]

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

Updated Linear Equation Project Idea

Tags:

alternative assessment,

project

One of the lesson ideas I recently rediscovered was a project I dubbed the "Linear Equation Formula Book". Student get to prove they can do the types of problems we've been focusing on throughout the unit in a way that doesn't seem like an assessment.

First, the kids create a "book" by folding two pieces of paper together (hamburger style). On each page, they'll write a title, a formula/steps to follow, and include their own completed example.

On my guide I include completed examples of each page and type of problem we've been focusing on:

I like this as an effective review (or a fun alternative assessment in and of itself) because students have to demonstrate that they can successfully do each of these types of problem. Either way, the book can stay with the students as a fun, accessible study guide for future state or end-of-year exams.

Download a PDF of my project directions below. This is designed to take about two 45-55 minute class periods at most.

Linear Equation Formula Book (new fall 2011 version)

Here's are two alternate versions you can also draw ideas from:

Linear Equation Formula Book (2009 version)

Project Idea: Using Formulas to Find Area, Perimeter and Circumference

First, the kids create a "book" by folding two pieces of paper together (hamburger style). On each page, they'll write a title, a formula/steps to follow, and include their own completed example.

On my guide I include completed examples of each page and type of problem we've been focusing on:

- Finding slope between two points

- Rewriting equations into slope-intercept form

- Finding an equation using point-slope form

- Graphing from slope-intercept form

- Finding x and y-intercepts

- Finding the slope of parallel and perpendicular lines

- Graphing linear inequalities

I like this as an effective review (or a fun alternative assessment in and of itself) because students have to demonstrate that they can successfully do each of these types of problem. Either way, the book can stay with the students as a fun, accessible study guide for future state or end-of-year exams.

Download a PDF of my project directions below. This is designed to take about two 45-55 minute class periods at most.

Linear Equation Formula Book (new fall 2011 version)

Here's are two alternate versions you can also draw ideas from:

Linear Equation Formula Book (2009 version)

Project Idea: Using Formulas to Find Area, Perimeter and Circumference

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)